Thursday, May 17, 2018

Wednesday, May 16, 2018

Book Review: James and Deborah Fallows' Our Towns (2018)

James Fallows' style is as close to the great James Michener as you can get. Unfortunately, he and his wife seem to have caught the "positivity vibe" at the expense of journalistic integrity. It's not that the couple lie--the Fallows are too sincere, too professional--but their blind spots function as a kind of concealment.

For example, Deborah Fallows discusses a Darfur refugee's "apparel" problem: "A big disappointment... was not being allowed to wear her hijab along with her ROTC uniform to school... she would have to choose." Mrs. Fallows then writes, sugary-sweetly, "It was beyond me, from my adult perspective, that this girl's preoccupying problem at sixteen years old was her apparel conflict." [Emphasis mine.] No mention of religious freedom exists anywhere on the page, nor a discussion about why the American government was forcing a Muslim refugee to choose between her religious beliefs and service to her country.

A more serious book would have directed the reader to the fact that military outfits despise exceptions to rules--uniformity is key to controlling actions and ensuring order. Instead, Deb Fallows uses the refugee's story as incontrovertible evidence America is working well. When she discussed the "apparel" issue during a recent interview, her husband, a devoted man whose love renders him incapable of correcting his wife's blind spots, saw the problem and immediately tried to save her by mentioning the local ROTC's request for a rule modification, which was eventually granted.

Throughout the book, I sensed Mr. Fallows gently trying to mitigate Mrs. Fallows' unbridled optimism in a uniquely WASPy way. Discussing Sioux Falls, South Dakota's current economy, Mr. Fallows describes the city's choice of institutions a long time ago: "Would it prefer to be the home of the state university? Or the state penitentiary? ... the penitentiary offered steadier work for locals, so that is what they took." Readers knowledgable about America's worldwide #1 incarceration rate--a massive, unresolved issue that sheds light on untrammeled police discretion in making arrests--can understand the background in context. My concern is many readers might be unfamiliar with Mr. Fallows' genial, non-confrontational style--he was President Carter's speechwriter, after all--and miss the understated intellectualism behind his words.

The Fallows are best when they stick to hard facts, such as their time operating a small aircraft; their research into ingenious ideas to melt snow (divert hot water from the cooling system of the local electric plant through plastic pipes under city streets and sidewalks); or historical color ("The Democratic-dominated city council tried to thwart every appointment, proposal, and piece of legislation [Bernie] Sanders put forward [after he won as an independent candidate by 10 votes]"). As it stands, if you read the Fallows' hefty book, just be aware of its selection bias. If you visit a city that knows you're coming and that has actively advertised itself to you, you'll get some version of a sanitized tour. (In one place, as soon as the Fallows land, they are greeted by "Captain Bob Peacock, one of many outsized personalities in the town.")

For her part, Ms. Fallows says in an interview, "If you want to know what's wrong or what's needed [in a city], ask the librarian." Yet, one imagines visiting any country's libraries would result in optimism, even in North Korea. Perhaps that's the point the Fallows are trying to make: in any country, despite its overall decline, you will find pockets of hope and optimism, and your job is to find those places.

I'll leave you with one of my favorite sentences, as an American immigrant hoping to live outside the United States one day: "Every city that is trendy or successful in some way attracts people from someplace else," which reveals America's economic engine as based on internal and external immigration.

|

| May 15, 2018 in Palo Alto, CA |

For example, Deborah Fallows discusses a Darfur refugee's "apparel" problem: "A big disappointment... was not being allowed to wear her hijab along with her ROTC uniform to school... she would have to choose." Mrs. Fallows then writes, sugary-sweetly, "It was beyond me, from my adult perspective, that this girl's preoccupying problem at sixteen years old was her apparel conflict." [Emphasis mine.] No mention of religious freedom exists anywhere on the page, nor a discussion about why the American government was forcing a Muslim refugee to choose between her religious beliefs and service to her country.

A more serious book would have directed the reader to the fact that military outfits despise exceptions to rules--uniformity is key to controlling actions and ensuring order. Instead, Deb Fallows uses the refugee's story as incontrovertible evidence America is working well. When she discussed the "apparel" issue during a recent interview, her husband, a devoted man whose love renders him incapable of correcting his wife's blind spots, saw the problem and immediately tried to save her by mentioning the local ROTC's request for a rule modification, which was eventually granted.

Throughout the book, I sensed Mr. Fallows gently trying to mitigate Mrs. Fallows' unbridled optimism in a uniquely WASPy way. Discussing Sioux Falls, South Dakota's current economy, Mr. Fallows describes the city's choice of institutions a long time ago: "Would it prefer to be the home of the state university? Or the state penitentiary? ... the penitentiary offered steadier work for locals, so that is what they took." Readers knowledgable about America's worldwide #1 incarceration rate--a massive, unresolved issue that sheds light on untrammeled police discretion in making arrests--can understand the background in context. My concern is many readers might be unfamiliar with Mr. Fallows' genial, non-confrontational style--he was President Carter's speechwriter, after all--and miss the understated intellectualism behind his words.

The Fallows are best when they stick to hard facts, such as their time operating a small aircraft; their research into ingenious ideas to melt snow (divert hot water from the cooling system of the local electric plant through plastic pipes under city streets and sidewalks); or historical color ("The Democratic-dominated city council tried to thwart every appointment, proposal, and piece of legislation [Bernie] Sanders put forward [after he won as an independent candidate by 10 votes]"). As it stands, if you read the Fallows' hefty book, just be aware of its selection bias. If you visit a city that knows you're coming and that has actively advertised itself to you, you'll get some version of a sanitized tour. (In one place, as soon as the Fallows land, they are greeted by "Captain Bob Peacock, one of many outsized personalities in the town.")

For her part, Ms. Fallows says in an interview, "If you want to know what's wrong or what's needed [in a city], ask the librarian." Yet, one imagines visiting any country's libraries would result in optimism, even in North Korea. Perhaps that's the point the Fallows are trying to make: in any country, despite its overall decline, you will find pockets of hope and optimism, and your job is to find those places.

I'll leave you with one of my favorite sentences, as an American immigrant hoping to live outside the United States one day: "Every city that is trendy or successful in some way attracts people from someplace else," which reveals America's economic engine as based on internal and external immigration.

Tuesday, May 15, 2018

Rafat's Law of Individual Freedom in an Era of Globalization

Only one law (or a variation thereof) seems likely to increase individual freedom by forcing countries to compete for citizens:

1. Any permanent resident or citizen of Country X with at least 15 billion USD in goods and/or services sold annually in at least 1 of the past 7 yrs to Country Y shall be allowed to move to Country Y and automatically gain the same legal residency status as in Country X, including but not limited to permanent residency or citizenship, unless

a) s/he has a conviction for a violent crime involving physical injury in the past 30 yrs; or

b) Country X's population is fewer than 20 million and/or has a population density [defined as persons per sq km except for refugees] greater than 550 at time of application; AND

Furthermore, such legal residency exchange shall only be allowed two times in any individual's lifetime; AND

All applications under this statute shall be processed within 7 days of receipt by Country X; AND

Furthermore, any denial must be in writing with rationale and documents supporting denial included, along with right to appeal within 60 days and appear before independent tribunal.

2. To prevent currency manipulations circumventing this statute's intent, residents of Country X moving to Country Y shall be entitled to receive any exchange rate over the last 11 years posted at the close of business by any government-insured banking entity with at least 50 billion USD in deposits or assets. Amounts may not be adjusted for inflation.

Update: re: FOREX rates, I envision some restrictions to prevent gaming, such as "...except that if residents moving from Country X to Country Y do not reside at least 200 days a year in Country Y for at least three consecutive years, Country Y may exercise a one-time right to demand FOREX transaction difference between actual exchanged rates and current rates on date of return, but such right shall not be used to deny a resident the right to return to Country X; instead, the difference shall be registered in an international court's ledgers using blockchain verification and any amount in excess of 25 million USD shall be transferred from Country X's escrow account into Country Y's account."

1. Any permanent resident or citizen of Country X with at least 15 billion USD in goods and/or services sold annually in at least 1 of the past 7 yrs to Country Y shall be allowed to move to Country Y and automatically gain the same legal residency status as in Country X, including but not limited to permanent residency or citizenship, unless

a) s/he has a conviction for a violent crime involving physical injury in the past 30 yrs; or

b) Country X's population is fewer than 20 million and/or has a population density [defined as persons per sq km except for refugees] greater than 550 at time of application; AND

Furthermore, such legal residency exchange shall only be allowed two times in any individual's lifetime; AND

All applications under this statute shall be processed within 7 days of receipt by Country X; AND

Furthermore, any denial must be in writing with rationale and documents supporting denial included, along with right to appeal within 60 days and appear before independent tribunal.

2. To prevent currency manipulations circumventing this statute's intent, residents of Country X moving to Country Y shall be entitled to receive any exchange rate over the last 11 years posted at the close of business by any government-insured banking entity with at least 50 billion USD in deposits or assets. Amounts may not be adjusted for inflation.

Update: re: FOREX rates, I envision some restrictions to prevent gaming, such as "...except that if residents moving from Country X to Country Y do not reside at least 200 days a year in Country Y for at least three consecutive years, Country Y may exercise a one-time right to demand FOREX transaction difference between actual exchanged rates and current rates on date of return, but such right shall not be used to deny a resident the right to return to Country X; instead, the difference shall be registered in an international court's ledgers using blockchain verification and any amount in excess of 25 million USD shall be transferred from Country X's escrow account into Country Y's account."

Monday, May 14, 2018

Courage over Nuance, Optics over Substance

I can't help but look for signs indicating whether America can reverse its suicidal tendencies post-9/11. Along the way, I've noticed actual signs indicating irreversible division in parts of the country. Here's a meaningless sticker I saw over the weekend:

It states, "I stand for our anthem." I don't disagree with the idea behind the bumper sticker--I, too, stand for our national anthem--but people in affluent, politically-stable countries don't put political ideas on bumper stickers. They're able to perform basic daily functions--driving, shopping, dating, etc.--without ideological wedges. I've visited 49 countries, and excepting President Duterte's election, I've yet to see a well-off Asian adult use political stickers.

The owner of the van lives in an affluent area near the beach and appears to own a business. His small house needed paint and repairs, and I didn't understand why anyone would want to buy handyman services from someone whose house didn't appear on the up and up. Then I realized the political sticker might be his way of being counter-culture and attracting like-minded customers. It cannot be easy being a minority in a college town so in-your-face liberal, even I, a tolerant sort of fellow, shudder at its leftism. Rainbow flags and pins are so common, you're surprised when you don't see them. How such signaling helps resolve deep-seated issues, including one of the highest rates of criminality in the country, is beyond me. (Hint: if it's easy to do, it probably doesn't do anything, something most of us learn after 30.)

Older business owners in the same city recently displayed large signs supporting local police as a response to perceived bias: "WE SUPPORT OUR POLICE." One wonders, "Is there anyone who doesn't support honest police officers?" Is the city of Santa Cruz, California arguing its police department has no corruption or its police union has a consistent history of removing poorly behaving officers more quickly and more efficiently than other cities? If so, that's one helluva bumper sticker, except, of course, such arguments won't fit on a bumper sticker. The lesson? Extremism attracts counter-reactions which go nowhere substantive because extremism by definition involves ideas tailor-made for bumper stickers: short, simple, and stupid. (On that note, the best political bumper stickers identify a specific problem, encouraging discussion--"It's the economy, stupid"--instead of choosing a side.)

Not coincidentally, I've noticed another common motif in modern America: lack of nuance.

After 9/11, the United States waterboarded members of a terrorist group it believed were linked to 9/11. It's unclear how many times waterboarding occurred, but it occurred between 5 and 15 times in sessions lasting up to 20 minutes each, and it's possible 83 to 183 applications of water were applied to simulate drowning over a three-week period. I'm not interested in the exact details because as we'll see, it doesn't matter as much as the lines governments cross in their cost-benefit analysis relating to potentially immoral actions.

The torture failed, based on the CIA's own documents, to produce actionable information. From The New Yorker: "No information provided by Mohammed led directly to the capture of a terrorist or the disruption of a terrorist plot." As typical in such scenarios, false information was provided because the detainee "simply told his interrogators what he thought they wanted to hear." Ultimately, in exchange for information that wasn't immediately actionable, the United States decided it was willing to risk its international standing and reputation--permanently.

Once a line has been crossed, everything tends to becomes harder in the absence of principles, increasing risks of greater and harsher counter-measures. Abu Ghraib, the site of American war crimes, didn't arise spontaneously. It took steady line crossing and an absence of principled leadership to get there. Sadly, we tend to forget principles preventing immoral actions in exchange for speculative benefits don't just protect "the other" side--they also protect you by preserving your reputation and increasing chances you'll receive viable information in the future.

After any incident damaging to a country's reputation, whether Abu Ghraib or widespread kneeling during the national anthem, a tactic to preserve citizen loyalty is to flood media with out-of-context activities or outliers, making it harder to ascertain full details. Disinformation has always been an intelligence agency tactic, but in an age where private and public actors can manipulate Google and Yahoo searches as well as your social media feeds, it's become pathological. For our purposes, we must understand the more false information, the less likely it is that groups will ever determine agreed-upon details and reach more difficult questions, including ones involving morality and transparency. The result? As long as people are divided against each other, existing power players and politicians can control the dialogue and character of a nation.

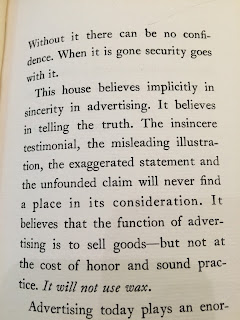

By now, we know we don't need to click on the link showing a Special Forces solider waterboarding himself to know he didn't do it anywhere near the number of times applied to a terrorist suspect, making his experiment worthless. A single pin prick might not constitute torture, but a hundred pin pricks without a definite end date is a different matter. The lesson: a country without firm principles will flounder and eventually fade away because any approach becomes justifiable. I will end with words on sincerity, misleading thoughts, and exaggerated statements from In Behalf of Advertising (1929):

It's only been 89 years, but it seems like such a long time ago. Does anyone know the Latin phrase for "Without bumper stickers"?

It states, "I stand for our anthem." I don't disagree with the idea behind the bumper sticker--I, too, stand for our national anthem--but people in affluent, politically-stable countries don't put political ideas on bumper stickers. They're able to perform basic daily functions--driving, shopping, dating, etc.--without ideological wedges. I've visited 49 countries, and excepting President Duterte's election, I've yet to see a well-off Asian adult use political stickers.

The owner of the van lives in an affluent area near the beach and appears to own a business. His small house needed paint and repairs, and I didn't understand why anyone would want to buy handyman services from someone whose house didn't appear on the up and up. Then I realized the political sticker might be his way of being counter-culture and attracting like-minded customers. It cannot be easy being a minority in a college town so in-your-face liberal, even I, a tolerant sort of fellow, shudder at its leftism. Rainbow flags and pins are so common, you're surprised when you don't see them. How such signaling helps resolve deep-seated issues, including one of the highest rates of criminality in the country, is beyond me. (Hint: if it's easy to do, it probably doesn't do anything, something most of us learn after 30.)

Older business owners in the same city recently displayed large signs supporting local police as a response to perceived bias: "WE SUPPORT OUR POLICE." One wonders, "Is there anyone who doesn't support honest police officers?" Is the city of Santa Cruz, California arguing its police department has no corruption or its police union has a consistent history of removing poorly behaving officers more quickly and more efficiently than other cities? If so, that's one helluva bumper sticker, except, of course, such arguments won't fit on a bumper sticker. The lesson? Extremism attracts counter-reactions which go nowhere substantive because extremism by definition involves ideas tailor-made for bumper stickers: short, simple, and stupid. (On that note, the best political bumper stickers identify a specific problem, encouraging discussion--"It's the economy, stupid"--instead of choosing a side.)

Not coincidentally, I've noticed another common motif in modern America: lack of nuance.

|

| Sunday, May 13, 2018, Yahoo.com front page |

The torture failed, based on the CIA's own documents, to produce actionable information. From The New Yorker: "No information provided by Mohammed led directly to the capture of a terrorist or the disruption of a terrorist plot." As typical in such scenarios, false information was provided because the detainee "simply told his interrogators what he thought they wanted to hear." Ultimately, in exchange for information that wasn't immediately actionable, the United States decided it was willing to risk its international standing and reputation--permanently.

Once a line has been crossed, everything tends to becomes harder in the absence of principles, increasing risks of greater and harsher counter-measures. Abu Ghraib, the site of American war crimes, didn't arise spontaneously. It took steady line crossing and an absence of principled leadership to get there. Sadly, we tend to forget principles preventing immoral actions in exchange for speculative benefits don't just protect "the other" side--they also protect you by preserving your reputation and increasing chances you'll receive viable information in the future.

After any incident damaging to a country's reputation, whether Abu Ghraib or widespread kneeling during the national anthem, a tactic to preserve citizen loyalty is to flood media with out-of-context activities or outliers, making it harder to ascertain full details. Disinformation has always been an intelligence agency tactic, but in an age where private and public actors can manipulate Google and Yahoo searches as well as your social media feeds, it's become pathological. For our purposes, we must understand the more false information, the less likely it is that groups will ever determine agreed-upon details and reach more difficult questions, including ones involving morality and transparency. The result? As long as people are divided against each other, existing power players and politicians can control the dialogue and character of a nation.

By now, we know we don't need to click on the link showing a Special Forces solider waterboarding himself to know he didn't do it anywhere near the number of times applied to a terrorist suspect, making his experiment worthless. A single pin prick might not constitute torture, but a hundred pin pricks without a definite end date is a different matter. The lesson: a country without firm principles will flounder and eventually fade away because any approach becomes justifiable. I will end with words on sincerity, misleading thoughts, and exaggerated statements from In Behalf of Advertising (1929):

It's only been 89 years, but it seems like such a long time ago. Does anyone know the Latin phrase for "Without bumper stickers"?

© Matthew Rafat (2018)

Bonus: "I am not educated, but I am sincere, and my sincerity is my credentials." -- Malcolm X

Bonus: "I am not educated, but I am sincere, and my sincerity is my credentials." -- Malcolm X

Friday, May 11, 2018

Christopher Moore at Kepler's Books in Menlo Park, CA

Christopher Moore can be described in one word: wacky. He's like Dave Barry, if Barry had no inhibitions.

Moore was at Kepler's Books promoting his new novel, Noir (2018). Before signing books, he gave a "commencement speech," hat and all, with several points of advice: "Face your fears... unless it's fire." And "You'll probably get VD [venereal disease] but not at the zoo. Probably."

It's unclear if Moore, who studied anthropology at Ohio State, graduated from any college. The Q&A session revealed other interesting tidbits. Moore's grandfather, a military veteran, loved to read. When out at sea, servicemen had lots of free time, and sometimes, his grandfather would read "a book a day." His love of reading passed down to his son, who became a police officer. Moore would observe his father reading at home and he, too, "read a lot." Moore's influences include Kurt Vonnegut, Tom Robbins, and Carl Hiassen (like Dave Barry, also a Miami Herald columnist).

What was he like as a teenager? "A smart*ss. No one likes a smart*ss and now I get paid to be one."

Will his novels ever be made into movies? Moore explained "getting optioned means nothing." In other words, just because someone or a company buys a book's movie rights doesn't mean a movie will get made. More likely, the option to make a film will be passed on or shopped around in perpetuity.

My favorite Moore book is Bloodsucking Fiends (1995) and I was disappointed in the sequel, You Suck (2007), which felt forced. As Moore became more popular, he sought inspiration by leaving the inner workings of his own mind and using details learned while traveling. I prefer Moore's unhinged comedy more than his reality-fantasy hybrid (e.g., he traveled to the Dead Sea to research a book about Christ's fictional childhood friend), but fans implored me to give Lamb (2002) a chance. I haven't read Noir (2018) yet, but it looks complex, and I'll probably write down all the different characters' names to keep them straight.

When it came time to sign my book, I asked him to sign it to "Bloodsucking Fiends." Moore, perhaps unaccustomed to someone wackier than himself, questioned why I wanted him to sign it that way, but eventually acquiesced, adding a quizzical "Okay!" He gave fans mini alien figures with his signature imprinted on the aliens' foreheads. Moore's wackiness is unparalleled but I wish he'd recapture the effortless humor he had when writing about his true interest: horror.

Moore was at Kepler's Books promoting his new novel, Noir (2018). Before signing books, he gave a "commencement speech," hat and all, with several points of advice: "Face your fears... unless it's fire." And "You'll probably get VD [venereal disease] but not at the zoo. Probably."

It's unclear if Moore, who studied anthropology at Ohio State, graduated from any college. The Q&A session revealed other interesting tidbits. Moore's grandfather, a military veteran, loved to read. When out at sea, servicemen had lots of free time, and sometimes, his grandfather would read "a book a day." His love of reading passed down to his son, who became a police officer. Moore would observe his father reading at home and he, too, "read a lot." Moore's influences include Kurt Vonnegut, Tom Robbins, and Carl Hiassen (like Dave Barry, also a Miami Herald columnist).

What was he like as a teenager? "A smart*ss. No one likes a smart*ss and now I get paid to be one."

Will his novels ever be made into movies? Moore explained "getting optioned means nothing." In other words, just because someone or a company buys a book's movie rights doesn't mean a movie will get made. More likely, the option to make a film will be passed on or shopped around in perpetuity.

My favorite Moore book is Bloodsucking Fiends (1995) and I was disappointed in the sequel, You Suck (2007), which felt forced. As Moore became more popular, he sought inspiration by leaving the inner workings of his own mind and using details learned while traveling. I prefer Moore's unhinged comedy more than his reality-fantasy hybrid (e.g., he traveled to the Dead Sea to research a book about Christ's fictional childhood friend), but fans implored me to give Lamb (2002) a chance. I haven't read Noir (2018) yet, but it looks complex, and I'll probably write down all the different characters' names to keep them straight.

When it came time to sign my book, I asked him to sign it to "Bloodsucking Fiends." Moore, perhaps unaccustomed to someone wackier than himself, questioned why I wanted him to sign it that way, but eventually acquiesced, adding a quizzical "Okay!" He gave fans mini alien figures with his signature imprinted on the aliens' foreheads. Moore's wackiness is unparalleled but I wish he'd recapture the effortless humor he had when writing about his true interest: horror.

Thursday, May 10, 2018

Bobby Douglas: the American Wrestling Legend You've Never Heard Of

Bobby Douglas is a great man--no reasonable person can disagree. He and his wife have made numerous sacrifices for the sport of wrestling, perhaps more than any other family not named Schultz.

After reading Craig Sesker's biography, you'll wonder why Mr. Douglas hasn't been awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Douglas was born poor and black in America when either trait should have confined him to a lifetime of neglect. Instead, despite his small stature, Douglas entered a wrestling mat, and the rest is history: "Wrestling is my best friend... it saved my life. I truly believe that. It saved my life." (pp. 172)

Younger wrestling fans will have difficulty remembering a time when Jordan Burroughs wasn't the face of American wrestling, or when Kevin Jackson and Kenny Monday weren't household names. Sesker's gift as a writer is ensuring you realize once upon a time, it was different: "Bobby Eddie Douglas was born near the beginning of WWII in Bellaire, Ohio. He was raised in nearby Blaine, a tiny eastern Ohio community of around 150 people." (pp. 14) "When his uncle returned home... from the Korean War with a white German wife, members of the KKK burned a cross... 'Everybody carried some sort of weapon to defend themselves...'" (pp. 21) "We were so hungry... I knew we were poor because I was always hungry." (pp. 42)

And it continues, cards so stacked against Douglas, you have to wonder if the Biblical Job had it easy by comparison: "His grandparents were illiterate. When they received letters in the mail, they handed them to a young Bobby to read to them." (pp. 21) Douglas even has a south side of Chicago connection: his aunt lived there, "in the ghetto," and used Douglas as a numbers "runner" in the summers: "Douglas would run gambling slips and collect money for the lottery.. At times, Douglas [a kid weighing about 50 pounds] would be carrying several hundred dollars in his pocket." (pp. 22-23)

At this point, I imagined a cross between LeBron James (born and raised in a small town in Ohio) and JAY-Z (also raised in the projects and who carried today's equivalent of hundreds of dollars, 2,000 USD, as a drug dealer), only to realize America's curse for poor young black men in any era: unless you develop a talent at the highest levels, you'll be stuck wherever you are because decades of segregation cut you off from opportunities others take for granted.

Despite his small town background, Douglas's warm, authentic personality helped him transition to different neighborhoods seamlessly, even in Tokyo. In every story, he is universally likable as a wrestler, recruiter, or coach. For example, Sesker tells us a story about Douglas up against the dirtiest coaches (and wrestlers) in America, the Brands brothers. After an opposing wrestler uses a dangerous and illegal move, Coach Douglas "felt [the] move was unintentional." (pp. 128) Everyone but Douglas seems to know the move was pre-meditated, even Sesker, who uses the word "illegal" four times on the page. Afterwards, an Ohio State wrestling coach informs Douglas, "That [injury default] was the wrong thing to do." (Id.) Douglas, of course, disagrees. In the end, the greatest American tactician not named John Smith refused to win on a technicality even when his own wrestler was injured in an illegal move. And on and on it goes, Douglas always being the better man, the reader feeling smaller and smaller with each passing page.

We find out Douglas is father to a child, now a man, suffering from paranoid schizophrenia; he coached the first West Coast college team to a national wrestling championship, only to be harassed by an incoming Arizona State athletic director for going 20,000 USD over budget; he feels responsible for the unexpected suicide of a wrestler he'd recruited ("I told [the parents] I'd take care of their son like he was my son"); and he remains married to his first girlfriend, Jackie.

The most unexpected story in the book involves one of Douglas's best students, Cael Sanderson. Sanderson was undefeated in college and today coaches America's top-ranked college wrestling program at Penn State. Douglas coached him to college and Olympic victories, but that wasn't enough for Sanderson to avoid placing his own interests above his coach's. After two years as an assistant coach under Douglas at Iowa State, Sanderson appears to have issued an ultimatum to Iowa State's athletic director, Jamie Pollard, demanding to be made head coach at Iowa State or he'd leave to Ohio State. Coach "Douglas still had three years left on his contract," but that didn't matter to Iowa State: "I'm willing to give you one more year," said Pollard. (pp. 148) And just like that, Douglas was out, and Sanderson in. Perhaps karma took notice, because Sanderson only coached at Iowa State three years, from 2006 to 2009, and then transferred to Penn State. At Iowa State, Sanderson failed to win a national championship.

Sesker has done an incredible job writing Douglas's story. His writing style is straightforward, making his book easily translatable into any language. I can think of only one other book that is similar, Jack August's Adversity is my Angel, about Raul H. Castro (who, interestingly, also has an Arizona connection). If I had my way, Sesker's and August's books would be required reading for every 9th grade American boy. For now, I hope you'll discover these gems on your own and gift them to your sons.

(Sesker's book is difficult to find online. You can reach him directly at sesker493 at yahoo.com to order a copy.)

After reading Craig Sesker's biography, you'll wonder why Mr. Douglas hasn't been awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Douglas was born poor and black in America when either trait should have confined him to a lifetime of neglect. Instead, despite his small stature, Douglas entered a wrestling mat, and the rest is history: "Wrestling is my best friend... it saved my life. I truly believe that. It saved my life." (pp. 172)

Younger wrestling fans will have difficulty remembering a time when Jordan Burroughs wasn't the face of American wrestling, or when Kevin Jackson and Kenny Monday weren't household names. Sesker's gift as a writer is ensuring you realize once upon a time, it was different: "Bobby Eddie Douglas was born near the beginning of WWII in Bellaire, Ohio. He was raised in nearby Blaine, a tiny eastern Ohio community of around 150 people." (pp. 14) "When his uncle returned home... from the Korean War with a white German wife, members of the KKK burned a cross... 'Everybody carried some sort of weapon to defend themselves...'" (pp. 21) "We were so hungry... I knew we were poor because I was always hungry." (pp. 42)

And it continues, cards so stacked against Douglas, you have to wonder if the Biblical Job had it easy by comparison: "His grandparents were illiterate. When they received letters in the mail, they handed them to a young Bobby to read to them." (pp. 21) Douglas even has a south side of Chicago connection: his aunt lived there, "in the ghetto," and used Douglas as a numbers "runner" in the summers: "Douglas would run gambling slips and collect money for the lottery.. At times, Douglas [a kid weighing about 50 pounds] would be carrying several hundred dollars in his pocket." (pp. 22-23)

At this point, I imagined a cross between LeBron James (born and raised in a small town in Ohio) and JAY-Z (also raised in the projects and who carried today's equivalent of hundreds of dollars, 2,000 USD, as a drug dealer), only to realize America's curse for poor young black men in any era: unless you develop a talent at the highest levels, you'll be stuck wherever you are because decades of segregation cut you off from opportunities others take for granted.

Despite his small town background, Douglas's warm, authentic personality helped him transition to different neighborhoods seamlessly, even in Tokyo. In every story, he is universally likable as a wrestler, recruiter, or coach. For example, Sesker tells us a story about Douglas up against the dirtiest coaches (and wrestlers) in America, the Brands brothers. After an opposing wrestler uses a dangerous and illegal move, Coach Douglas "felt [the] move was unintentional." (pp. 128) Everyone but Douglas seems to know the move was pre-meditated, even Sesker, who uses the word "illegal" four times on the page. Afterwards, an Ohio State wrestling coach informs Douglas, "That [injury default] was the wrong thing to do." (Id.) Douglas, of course, disagrees. In the end, the greatest American tactician not named John Smith refused to win on a technicality even when his own wrestler was injured in an illegal move. And on and on it goes, Douglas always being the better man, the reader feeling smaller and smaller with each passing page.

We find out Douglas is father to a child, now a man, suffering from paranoid schizophrenia; he coached the first West Coast college team to a national wrestling championship, only to be harassed by an incoming Arizona State athletic director for going 20,000 USD over budget; he feels responsible for the unexpected suicide of a wrestler he'd recruited ("I told [the parents] I'd take care of their son like he was my son"); and he remains married to his first girlfriend, Jackie.

The most unexpected story in the book involves one of Douglas's best students, Cael Sanderson. Sanderson was undefeated in college and today coaches America's top-ranked college wrestling program at Penn State. Douglas coached him to college and Olympic victories, but that wasn't enough for Sanderson to avoid placing his own interests above his coach's. After two years as an assistant coach under Douglas at Iowa State, Sanderson appears to have issued an ultimatum to Iowa State's athletic director, Jamie Pollard, demanding to be made head coach at Iowa State or he'd leave to Ohio State. Coach "Douglas still had three years left on his contract," but that didn't matter to Iowa State: "I'm willing to give you one more year," said Pollard. (pp. 148) And just like that, Douglas was out, and Sanderson in. Perhaps karma took notice, because Sanderson only coached at Iowa State three years, from 2006 to 2009, and then transferred to Penn State. At Iowa State, Sanderson failed to win a national championship.

Sesker has done an incredible job writing Douglas's story. His writing style is straightforward, making his book easily translatable into any language. I can think of only one other book that is similar, Jack August's Adversity is my Angel, about Raul H. Castro (who, interestingly, also has an Arizona connection). If I had my way, Sesker's and August's books would be required reading for every 9th grade American boy. For now, I hope you'll discover these gems on your own and gift them to your sons.

(Sesker's book is difficult to find online. You can reach him directly at sesker493 at yahoo.com to order a copy.)

Wednesday, May 9, 2018

Propaganda, Brought by Your Own Tax Dollars

Former President Obama (2018): "Special interests, foreign governments, etc. can, in fact, manipulate and propagandize." What if at least one of those special interests is your own government? In Peter Richardson's A Bomb in Every Issue (2009), we learn the CIA directly or indirectly funded numerous liberal and conservative organizations, including ones with Gloria Steinem, the AFL-CIO, and William F. Buckley, Jr.

Problematically, we don't know which cultural change organizations weren't funded by the CIA. In other words, government interference may have cost Americans leaders who could have delivered more honest or less divisive commentary but who didn't have the numbers or influence at the exact time of the CIA's involvement. Funding x rather than y meant anything independent--anything related to y and not x--was at a disadvantage, tilting the media towards CIA-picked cultural leaders. As a result, almost everything you see and read might have been curated for you by a secretive, non-transparent government agency. If that's not propaganda, what is? And why isn't the president of the United States talking about it?

Bonus: "The agency's goals were to counter similar groups under Soviet control abroad and to recruit foreign students." The only reason we know any of this is because an insider--we'd call him a whistleblower today--hadn't signed an NDA and provided documents to a journalist at an independent publication. The independent publication, The Ramparts, had a distinctive strategy: raise hell and keep on raising it until national media, always late to the game, finally picked up the story.

Bonus: a world where secretive organizations can manipulate winners requires not just irresponsible funding but online manipulation (SEO, etc.). If the top 25 hits on Google's search engine can be curated for you by one or more intelligence organizations, can you believe anything you see and hear?

Problematically, we don't know which cultural change organizations weren't funded by the CIA. In other words, government interference may have cost Americans leaders who could have delivered more honest or less divisive commentary but who didn't have the numbers or influence at the exact time of the CIA's involvement. Funding x rather than y meant anything independent--anything related to y and not x--was at a disadvantage, tilting the media towards CIA-picked cultural leaders. As a result, almost everything you see and read might have been curated for you by a secretive, non-transparent government agency. If that's not propaganda, what is? And why isn't the president of the United States talking about it?

Bonus: "The agency's goals were to counter similar groups under Soviet control abroad and to recruit foreign students." The only reason we know any of this is because an insider--we'd call him a whistleblower today--hadn't signed an NDA and provided documents to a journalist at an independent publication. The independent publication, The Ramparts, had a distinctive strategy: raise hell and keep on raising it until national media, always late to the game, finally picked up the story.

Bonus: a world where secretive organizations can manipulate winners requires not just irresponsible funding but online manipulation (SEO, etc.). If the top 25 hits on Google's search engine can be curated for you by one or more intelligence organizations, can you believe anything you see and hear?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)