I can't help but look for signs indicating whether America can reverse its suicidal tendencies post-9/11. Along the way, I've noticed actual signs indicating irreversible division in parts of the country. Here's a meaningless sticker I saw over the weekend:

It states, "I stand for our anthem." I don't disagree with the idea behind the bumper sticker--I, too, stand for our national anthem--but people in affluent, politically-stable countries don't put political ideas on bumper stickers. They're able to perform basic daily functions--driving, shopping, dating, etc.--without ideological wedges. I've visited 49 countries, and excepting President Duterte's election, I've yet to see a well-off Asian adult use political stickers.

The owner of the van lives in an affluent area near the beach and appears to own a business. His small house needed paint and repairs, and I didn't understand why anyone would want to buy handyman services from someone whose house didn't appear on the up and up. Then I realized the political sticker might be his way of being counter-culture and attracting like-minded customers. It cannot be easy being a minority in a college town so in-your-face liberal, even I, a tolerant sort of fellow, shudder at its leftism. Rainbow flags and pins are so common, you're surprised when you don't see them. How such signaling helps resolve deep-seated issues, including one of the highest rates of criminality in the country, is beyond me. (Hint: if it's easy to do, it probably doesn't do anything, something most of us learn after 30.)

Older business owners in the same city recently displayed large signs supporting local police as a response to perceived bias: "WE SUPPORT OUR POLICE." One wonders, "Is there anyone who doesn't support honest police officers?" Is the city of Santa Cruz, California arguing its police department has no corruption or its police union has a consistent history of removing poorly behaving officers more quickly and more efficiently than other cities? If so, that's one helluva bumper sticker, except, of course, such arguments won't fit on a bumper sticker. The lesson? Extremism attracts counter-reactions which go nowhere substantive because extremism by definition involves ideas tailor-made for bumper stickers: short, simple, and stupid. (On that note, the best political bumper stickers identify a specific problem, encouraging discussion--"It's the economy, stupid"--instead of choosing a side.)

Not coincidentally, I've noticed another common motif in modern America: lack of nuance.

After 9/11, the United States waterboarded members of a terrorist group it believed were linked to 9/11. It's unclear how many times waterboarding occurred, but it occurred between 5 and 15 times in sessions lasting up to 20 minutes each, and it's possible 83 to 183 applications of water were applied to simulate drowning over a three-week period. I'm not interested in the exact details because as we'll see, it doesn't matter as much as the lines governments cross in their cost-benefit analysis relating to potentially immoral actions.

The torture failed, based on the CIA's own documents, to produce actionable information. From The New Yorker: "No information provided by Mohammed led directly to the capture of a terrorist or the disruption of a terrorist plot." As typical in such scenarios, false information was provided because the detainee "simply told his interrogators what he thought they wanted to hear." Ultimately, in exchange for information that wasn't immediately actionable, the United States decided it was willing to risk its international standing and reputation--permanently.

Once a line has been crossed, everything tends to becomes harder in the absence of principles, increasing risks of greater and harsher counter-measures. Abu Ghraib, the site of American war crimes, didn't arise spontaneously. It took steady line crossing and an absence of principled leadership to get there. Sadly, we tend to forget principles preventing immoral actions in exchange for speculative benefits don't just protect "the other" side--they also protect you by preserving your reputation and increasing chances you'll receive viable information in the future.

After any incident damaging to a country's reputation, whether Abu Ghraib or widespread kneeling during the national anthem, a tactic to preserve citizen loyalty is to flood media with out-of-context activities or outliers, making it harder to ascertain full details. Disinformation has always been an intelligence agency tactic, but in an age where private and public actors can manipulate Google and Yahoo searches as well as your social media feeds, it's become pathological. For our purposes, we must understand the more false information, the less likely it is that groups will ever determine agreed-upon details and reach more difficult questions, including ones involving morality and transparency. The result? As long as people are divided against each other, existing power players and politicians can control the dialogue and character of a nation.

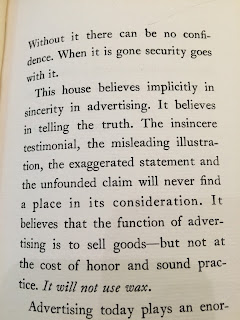

By now, we know we don't need to click on the link showing a Special Forces solider waterboarding himself to know he didn't do it anywhere near the number of times applied to a terrorist suspect, making his experiment worthless. A single pin prick might not constitute torture, but a hundred pin pricks without a definite end date is a different matter. The lesson: a country without firm principles will flounder and eventually fade away because any approach becomes justifiable. I will end with words on sincerity, misleading thoughts, and exaggerated statements from In Behalf of Advertising (1929):

It's only been 89 years, but it seems like such a long time ago. Does anyone know the Latin phrase for "Without bumper stickers"?

It states, "I stand for our anthem." I don't disagree with the idea behind the bumper sticker--I, too, stand for our national anthem--but people in affluent, politically-stable countries don't put political ideas on bumper stickers. They're able to perform basic daily functions--driving, shopping, dating, etc.--without ideological wedges. I've visited 49 countries, and excepting President Duterte's election, I've yet to see a well-off Asian adult use political stickers.

The owner of the van lives in an affluent area near the beach and appears to own a business. His small house needed paint and repairs, and I didn't understand why anyone would want to buy handyman services from someone whose house didn't appear on the up and up. Then I realized the political sticker might be his way of being counter-culture and attracting like-minded customers. It cannot be easy being a minority in a college town so in-your-face liberal, even I, a tolerant sort of fellow, shudder at its leftism. Rainbow flags and pins are so common, you're surprised when you don't see them. How such signaling helps resolve deep-seated issues, including one of the highest rates of criminality in the country, is beyond me. (Hint: if it's easy to do, it probably doesn't do anything, something most of us learn after 30.)

Older business owners in the same city recently displayed large signs supporting local police as a response to perceived bias: "WE SUPPORT OUR POLICE." One wonders, "Is there anyone who doesn't support honest police officers?" Is the city of Santa Cruz, California arguing its police department has no corruption or its police union has a consistent history of removing poorly behaving officers more quickly and more efficiently than other cities? If so, that's one helluva bumper sticker, except, of course, such arguments won't fit on a bumper sticker. The lesson? Extremism attracts counter-reactions which go nowhere substantive because extremism by definition involves ideas tailor-made for bumper stickers: short, simple, and stupid. (On that note, the best political bumper stickers identify a specific problem, encouraging discussion--"It's the economy, stupid"--instead of choosing a side.)

Not coincidentally, I've noticed another common motif in modern America: lack of nuance.

|

| Sunday, May 13, 2018, Yahoo.com front page |

The torture failed, based on the CIA's own documents, to produce actionable information. From The New Yorker: "No information provided by Mohammed led directly to the capture of a terrorist or the disruption of a terrorist plot." As typical in such scenarios, false information was provided because the detainee "simply told his interrogators what he thought they wanted to hear." Ultimately, in exchange for information that wasn't immediately actionable, the United States decided it was willing to risk its international standing and reputation--permanently.

Once a line has been crossed, everything tends to becomes harder in the absence of principles, increasing risks of greater and harsher counter-measures. Abu Ghraib, the site of American war crimes, didn't arise spontaneously. It took steady line crossing and an absence of principled leadership to get there. Sadly, we tend to forget principles preventing immoral actions in exchange for speculative benefits don't just protect "the other" side--they also protect you by preserving your reputation and increasing chances you'll receive viable information in the future.

After any incident damaging to a country's reputation, whether Abu Ghraib or widespread kneeling during the national anthem, a tactic to preserve citizen loyalty is to flood media with out-of-context activities or outliers, making it harder to ascertain full details. Disinformation has always been an intelligence agency tactic, but in an age where private and public actors can manipulate Google and Yahoo searches as well as your social media feeds, it's become pathological. For our purposes, we must understand the more false information, the less likely it is that groups will ever determine agreed-upon details and reach more difficult questions, including ones involving morality and transparency. The result? As long as people are divided against each other, existing power players and politicians can control the dialogue and character of a nation.

By now, we know we don't need to click on the link showing a Special Forces solider waterboarding himself to know he didn't do it anywhere near the number of times applied to a terrorist suspect, making his experiment worthless. A single pin prick might not constitute torture, but a hundred pin pricks without a definite end date is a different matter. The lesson: a country without firm principles will flounder and eventually fade away because any approach becomes justifiable. I will end with words on sincerity, misleading thoughts, and exaggerated statements from In Behalf of Advertising (1929):

It's only been 89 years, but it seems like such a long time ago. Does anyone know the Latin phrase for "Without bumper stickers"?

© Matthew Rafat (2018)

Bonus: "I am not educated, but I am sincere, and my sincerity is my credentials." -- Malcolm X

Bonus: "I am not educated, but I am sincere, and my sincerity is my credentials." -- Malcolm X

No comments:

Post a Comment