[Part 1 is HERE.]

|

| Muhammad Ali Museum, Louisville, KY |

H4: Well, obviously, Americans' ignorance of two essential economic terms: 1) inflation; and 2) interest rates. But even when we analyzed whether Americans understood the most basic functions of government, they all seemed to fail.

In 2018, a prominent politician, Elizabeth Warren, said, "Budgets aren't just numbers on a page. Budgets are about values. And over the past few months, I've fought tooth and nail for Congress to pass a budget deal that reflects our values."

Her statement is so obviously wrong, she should have been laughed out of office. Consider 2008-2009. The budget, which incentivizes behavior through taxation, "valued" home ownership. If values were your primary focus, then the budget and tax code already encouraged home ownership--a policy that ended in disaster and numerous foreclosures. That's one clue budgets shouldn't be based on values, but so many reasonable objections exist against government spending promoting subjective values, I couldn't possibly list them all. (What if the government wanted to "value" same-sex, opposite sex, or even no-sex marriages?)

In addition, if budgets were about values rather than sustainably supporting an interlinked ecosystem of jobs, then the primary value America stood for in 2018 was the military-industrial complex. What did Warren--who had family members in the military--want to do with military spending? Increase it. She voted for a military budget higher than what the pro-military president requested.

H3: Remind me, Warren was a conservative like America's President in 2018, right?

H4: Actually, she was a Harvard law professor and liberal, and her party sought to nominate her to run against the conservative, pro-military incumbent.

H3: Wait, what?

H4: The military-industrial complex had completely taken over America by 2018. Orwell's Animal Farm, taught in most secondary schools, had come to life: “The creatures outside looked from pig to man, and from man to pig, and from pig to man again; but already it was impossible to say which was which.”

Worse, the so-called conservative president wasn't conservative with the budget. His proposals required borrowing one trillion dollars.

H3: How could people get away with such blatant misrepresentations?

H4: Because all the numbers were wrong.

|

| Jim Rogers, Street Smarts (2013) |

H4: Let me give you an example. Governments, to increase efficiency, began placing certain services for auction. The lowest bid containing the essential scope of services would be chosen.

H3: That sounds like a great idea.

H4: It was--if you could count on people being honest about numbers. In reality, firms would make low bids and interpret the 3 to 10 years contract (called a Master Services Agreement) as not covering much of the necessary work. So if something wasn't specifically included in the original bid or proposal, the firm would do a change order or new mini-contract with additional fees. Basically, the original bid was never the final price. Governments and their service providers added contingencies for unexpected work, but as contracts reached expiration, fewer workers were needed to provide services. In short, the contract envisioned deteriorating customer service and responsiveness over time, coinciding with the service provider's ability to become entrenched.

Complicating matters, the government itself didn't always know the full scope of the projects or its reasonable costs. Some cities would hire outside experts like city managers, but most politicians were lawyers, not construction workers, scientists, electricians, or database managers.

H3: So why privatize? Why not keep the old system?

H4: The catalyst for privatization and outsourcing/insourcing was because government employees had become corrupt under the status quo. They voted themselves benefits unavailable to most private workers and then back-ended their compensation in ways that made balancing a budget unpredictable and more dependent on debt. Every price quoted for any government work, even if completed on time, understated true costs because it failed to include long-term benefit costs.

No one expected the private sector to become as corrupt and as unaccountable as the public sector. Yet, regardless of who was leading infrastructure projects, they always exceeded initial costs. It's like someone once said: everyone was in on it.

H4: What does that mean?

H3: It means things don't get progressively worse unless all resistance is removed. In order to prevent resistance, one can either eliminate or co-opt obstacles.

By 2018, the media--more specifically investigative journalism--and the American legal system, essential to keeping the executive branch in check, had been totally co-opted by the Establishment. Even renowned reporters like Lara Logan were hoodwinked by intelligence analysts into reporting fake news. With newspaper journalism slowly decaying into irrelevance, and the most respected television news outlet having published fake news, the public tuned out or began entertaining non-mainstream sources.

|

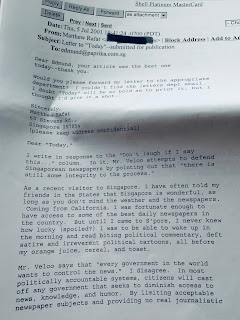

| From 2001. By 2019, the reverse was true: most developing countries had better news outlets than most developed ones. |

With Russia, the link was real but tenuous. The real goal was to deflect attention from WikiLeaks/Julian Assange, which had received intercepted cables from various hacker outfits, including hackers affiliated with Russia. These classified cables showed U.S. forces firing on ambulances (see 2007 Baghdad massacre, Ethan McCord, "Collateral Murder") while possibly gaming the rules-of-engagement process designed to prevent civilian deaths. (Short version, assuming audio wasn't added: an Apache pilot under no actual threat could easily receive shoot-to-kill clearance by claiming in comms he saw an RPG even if the RPG had no reasonable chance of being fired or making contact.)

H4: You're jumping all over the place.

H3: I'm trying to show that America's strategy in 2018 was to deliberately avoid the truth, which was reasonable in light of the fact that no one really understood the various risks in the interlinked global financial system.

Our key lesson is that everything that happens, even evil actions, are logical results. If Americans didn't or couldn't understand why their medical bills, education bills, etc., were going up every year without any corresponding increase in quality of life, why wouldn't it make sense to blame outsiders? Why wouldn't it make sense to try to disengage from an uncertain global system?

H4: But America benefited the most from the global system.

H3: True, from 1945 to 2001, the world was America's oyster. "When the war [WWII] ended, the United States accounted for two-thirds of the world's industrial output. In 1950, 60 percent of the capital stock of the advanced capitalist world was American. That same year, U.S. corporations accounted for one-third of the world's total GNP." Over time, America realized its greatest strength was using its military, especially its Navy, to control world trade through oil exports, which made its currency the de facto unit of exchange worldwide.

H4: "In debt we trust."

H3: Exactly--as long as that debt was backed by the U.S. dollar.

H4: Something tells me China wasn't too keen on this arrangement.

H3: Of course not. "He who has the gold makes the rules," except the "gold" changes every so often. In some places, it was cacao beans; in other places, corn; and still in other places it was pieces of paper granting ownership in companies. Today, it's data. Some pods still use oil, but for the most part, everything today runs on data.

H4: I am starting to feel sorry for these Americans.

H3: I keep trying to tell you--everyone, good, bad, smart, stupid, was in on it. French philosopher Jean Baudrillard summarized America's situation even better than Neil Postman and George Orwell. Imagine a society where everyone could identify Einstein but almost no one could explain anything he discovered, and where the lowest gambler to the highest Supreme Court justice needed debt to survive.

Allow me two stories. In the 21st century, an unknown Iranian-British-American writer knew two people very well. One of them used to be his best friend. He saw his friend, from a privileged family, go to law school and then get a government job regulating securities. On the way to the civilian job at the SEC, this friend--very pro-military and whose father saw active combat--signed up for a graduate degree while working as a Navy JAG to avoid being deployed to Iraq.

He bought his way out of being deployed but you won't find anyone more genuinely pro-military than him. When he received the job at the SEC regulating securities, he may have even benefited from federal laws promoting employment of military personnel. The icing on the cake? When he joined the SEC, he had almost zero understanding of securities. He'd never traded a security and couldn't tell you anything about finance in general.

H4: So a lawyer in charge of regulating the stock market and Wall Street was clueless about both?

H3: Yes, but remember: this was one of the best Americans the country produced. A good father, a good man. You'd want him working for you. And yet, it's easy to draw a line straight from the SEC/DOJ employment process to the 2008 financial crisis.

[Editor's note: "The grand total of prison sentences that resulted from a decade of S.E.C. referrals was 87... By 2002, only about one thousand white-collar criminals were in federal prison, less than 1 percent of the total federal prison population." -- from The Number (2004 paperback) by Alex Berenson, pp. 145.]

Another friend was the opposite of the one I just mentioned. His mother left him when he was young, but his father worked hard and eventually became successful. By the time the friend was in his 20s, he'd passed the bar exam but committed an ethical violation that caused his license to be suspended. He was possibly an alcoholic as well. Around 2008-2009, when housing prices collapsed in America, his family helped him buy a home below market price. And just like that, he became affluent. He even managed to reclaim his license to practice law after attending counseling.

But this friend isn't someone you'd want your son to emulate. He had little interest in raising his children when they were under 4 years old, and he married an immigrant dependent on him. At one point, when his wife said something he didn't like, he left abruptly without saying where he was going, leaving her with two young children. Before he returned, she called the writer, distraught, asking the whereabouts of her husband. Note that we are discussing one of the most successful middle managers in a large, well-known software company. I won't even get into the American president's administration at the time, which included Rob Porter. So whether you analyze the private or public sectors, nothing was working very well. Both seemed to promote incompetence or indifference.

Even nonprofits, unions, and religious institutions were failing. The Catholic Church in America paid billions in settlements after deliberately covering up child abuse and pedophilia. Child abuse!

|

| From 6/2019's The Atlantic, by James Carroll |

H3: I'm starting to understand what you mean when you say, "Everyone was in on it," but surely there were success stories.

H4: Of course there were, but it wasn't common. When someone managed to do well without an obvious assist, the media lionized that person, using outliers to create and market the image that a certain place was unique in its ability to elevate the poor into riches.

H3: We learned about this. By 2018, America had become a society of entrenched wealth, with little intergenerational mobility. Bill Gates' father was a successful lawyer. Warren Buffett's father was a 4-term U.S. Representative. Charlie Munger's grandfather was a federal judge. Elon Musk's father, Errol Musk, once said, "We were very wealthy. We had so much money at times we couldn't even close our safe."

But it wasn't just billionaires. In 1992, economists Daphne Greenwood and Edward Wolff "estimated that 50 to 70% of the wealth of households under age 50 was inherited."

|

| From Kwame Appiah's The Lies that Bind (2018): "In China, too, wealth and status is 80% determined... by the wealth and status of your parents." |

|

| Galloway's The Four (2017) |

H3: "Image is everything."

H4: Exactly. Now do you see why politicians were blaming Facebook and Russia in 2018 instead of trying to reform fundamental issues? As long as the problem is elsewhere, they don't look like fools being led to irrelevance.

At the same time, we should remember marketing drove much of America's consumer economy, so image really did matter. If I can buy virtually the same shoe, the same t-shirt, etc., from a Chinese or Japanese company online and pay less, why would I buy an American-made product? Fortunately, by 2018, most consumers had caught on to the marketing machine. In other words, it wasn't just fake news that repelled them--everything marketed falsely turned them off.

Smaller companies started to look more attractive by manufacturing less. Thus, self-imposed economic scarcity with higher personalization became the norm, sometimes even with excellent customer service. Consumers realized they could "signal" an image without major corporations, and small businesses realized they couldn't compete with larger corporations' ability to scale, so you had an economy that forked but became even more dependent on image.

H3: That doesn't seem optimal, especially if one's economy is consumer-driven.

H4: True. America faced having to create an entirely new business model, but how could it create a new economy when debt still drove every avenue? Technology companies were ahead of the curve--for decades, they had produced the majority of their revenue from overseas. By 2018, small businesses worldwide finally caught on and started using technological advances to also sell and invest overseas. The trillion dollar economic question became, "Which platforms would succeed? Amazon? Alibaba? Etsy? Aliexpress.com?"

H3: So the platform became the most important economic weapon?

H4: Yes. It's interesting you use the term, "weapon," because shipping still had to be effectuated properly, which required global cooperation. If a small or large business couldn't deliver its products efficiently, or if a single customs agent was incompetent, a business would decline even if it succeeded in being noticed online. Amazon predicted this development and began its own shipping business. For truly global trade to occur, shipping and logistics became key drivers.

As shipping became more efficient, people started questioning the global economic system's overseers and rule-makers. Why shouldn't Albanian mountain water or Georgian mineral water be able to compete on the same level playing field as water from Fiji or Iceland? Why should a few trade negotiators and presidents make it easier for one product to enter a country over another? Why shouldn't consumers in America, Cuba, and China have unfettered access to Iranian saffron and Persian pistachios?

H3: You're suggesting something radical. At the time, the basis for trade agreements and free trade zones--and their lower and preferential tariffs--was military and security cooperation as well as mutually beneficial weapons purchases. Trade was weaponized as a way to force weaker countries not part of a particular framework to adapt or come to the table and negotiate.

H4: Yes, but why? Why should the global economy be weaponized and based on military spending?

H3: Because if Country A had fewer security safeguards, its ability to ship containers to Country B increases risks for Country B's citizens. Human trafficking, weapons sales...

H4: But human trafficking and weapons sales were happening regardless of trade agreements and tariffs. The mafia would pay off the right people, squeeze others, and co-opt whatever security apparatus was in place.

Wherever human beings exist, so does the potential for corruption. Isn't that why fully automated systems captured the public's imagination in 2017? If you could remove human beings from the equation, you could increase safety and time. The tradeoffs would be less independence, less individuality, and less personalization--but if it worked for self-driving cars, why not shipping containers? After all, "90% of the world's commercial traffic is transported in containers on the high seas." (McMafia (2008), pp. 339)

Unfortunately, Americans underestimated the level of institutional corruption. Few people part of the security or global trade apparatus supported legalization of drugs or smoother legal immigration because as long as a mafia or enemy existed, law enforcement and military spending could increase or at least be maintained. On the federal/national level, military spending at some point provided 13.4% of jobs for American men. On the local/city level, at least 50%--and often 70+%--of the budget went to public safety aka police and firefighters. In some cities, even primary school crossing guards were being hired through the city's police budget.

So let's pretend humans in 2019 awoke to a world of peace and fully automated trade systems. How could their governments provide jobs and the taxes that produced the cash flow to maintain trillions of dollars of outstanding debt? How could the military and banking institutions, which had contributed so much to progress from 1945 to 2001, get their due?

H3: But by 2018, drones and other technological innovations meant fewer soldiers were needed, and the Western-debt-fueled model was unsustainable.

H4: So what? Don't you remember? Everyone was in on it. Image was everything. So how do you sustain such a model? You make sure everyone gets paid.

Consider something as simple as tobacco sales. Everyone knows tobacco is terrible for you. Your body rejects it immediately the first time you try it. But if you create a system where everyone from the local pharmacy to the local teacher to the national government gets paid--through sales taxes or direct sale revenue--then why would anyone be against tobacco? To be against tobacco, you'd have to replace the revenue on multiple levels with something else. That "something else" might be unpredictable.

[Editor's note: "In 1912, the [American] government derived 45% of its revenue from duties imposed on imported goods, and another 42% from excise taxes on alcohol and tobacco. There was no income tax. So tariffs and these two excise taxes accounted for 87% of government receipts. They were a kind of national sales tax, though no one called them that." -- Donald Bartlett & James Steele, The Great American Tax Dodge (2000), hardcover, pp. 6.]

H3: "The devil you know is better than the devil you don't"?

H4: Exactly. There's no conspiracy, no evil intent. But slowly everyone buys into an interlinked web of revenue, and once debt gets added in...

H3: The debt must be paid. Now I understand political pundit James Carville: “I used to think if there was reincarnation, I wanted to come back as the president or the pope or a .400 baseball hitter. But now I want to come back as the bond market. You can intimidate everybody.”

H4: Ha! You know something else? By 2018, Muslims already had the solution for over 1,000 years, or at least a mitigation strategy: a partnership investment model rather than a debt-via-slavery one. The followers of Muhammad (PBUH), many of them business-savvy, must have heard of Christian Jubilee(s) and innovated. Without realizing it, they invented the modern venture capital model, later perfected by Silicon Valley's Tom Perkins.

H3: So the Americans, they figured out the Muslims had the right idea and adapted?

H4: [Sigh.] No. They and their allies killed or tortured as many Muslims as they possibly could. Also, their President actively sought to ban them from entering the country. (See Executive Order 13769.)

H3: The courts went along with it?

H4: What do I keep telling you? Everyone was in on it. You think judges in Nazi Germany didn't go along with political leadership? (Jörg Friedrich: "Perhaps there is truly evidence that a constitutional state can stand on a judicial mass grave.") It's the same everywhere, in every time period.

[Editor's Note (February 15, 2018): the day after this post was published, a U.S. Court of Appeals voted 9-4 against revised Executive Order 13769. From Chief Judge Roger L. Gregory:

On a human level, the Proclamation’s invisible yet impenetrable barrier denies the possibility of a complete, intact family to tens of thousands of Americans. On an economic level, the Proclamation inhibits the normal flow of information, ideas, resources, and talent between the Designated [Muslim-majority] Countries and our schools, hospitals, and businesses. On a fundamental level, the Proclamation second-guesses our nation’s dedication to religious freedom and tolerance. "The basic purpose of the religion clause of the First Amendment is to promote and assure the fullest possible scope of religious liberty and tolerance for all and to nurture the conditions which secure the best hope of attainment of that end." Schempp, 374 U.S. at 305 (Goldberg, J., concurring). When we compromise our values as to some, we shake the foundation as to all. More here.]

[Editor's Note (July 1, 2018): In the end, everyone really was in on it. On June 26, 2018, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the travel ban in Trump vs. Hawaii (2018). Justice Sotomayor's and Justice Breyer's dissents are so obviously correct, and Justice Robert's opinion so obviously circular, the decision represents the last nail in the coffin for American cultural leadership. Every woman and Jew voted against the majority opinion; every Christian man voted in favor. Only one minority, an African-American man who attended private, white-majority Catholic high school and college, voted with the majority.]

Here's another quote you might like: "It seems that mankind is too stupid and too greedy to save himself." It was repeated verbatim by Stephen Hawking decades later. I'm no physicist, but inertia is the most powerful force I've studied, especially when the human ego is involved.

H3: This is getting depressing. It couldn't possibly have been that bad, because otherwise, we wouldn't be here discussing our ancestors, right?

H4: Progress doesn't require happiness. A machine can continue regardless of its emotional state, and the American economy was very much like a machine, with workers in debt having no choice but to be optimistic.

H3: I don't agree with you. I've studied the humans, too, and they produced wonderful art and were capable of great acts of charity. I'll give you a quote now, from Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.: "The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice."

H4: Dr. King didn't invent that quote, but I like his other ones better:

"A few years ago there was a shining moment in that struggle. It seemed as if there was a real promise of hope for the poor--both black and white--through the poverty program. There were experiments, hopes, new beginnings. Then came the buildup in Vietnam and I watched the program broken and eviscerated as if it were some idle political plaything of a society gone mad on war, and I knew that America would never invest the necessary funds or energies in rehabilitation of its poor so long as adventures like Vietnam continued to draw men and skills and money like some demonic destructive suction tube. So I was increasingly compelled to see the war as an enemy of the poor and to attack it as such... I knew that I could never again raise my voice against the violence of the oppressed in the ghettos without having first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today--my own government...

I am convinced that if we are to get on the right side of the world revolution, we as a nation must undergo a radical revolution of values. We must rapidly begin the shift from a 'thing-oriented' society to a 'person-oriented' society. When machines and computers, profit motives and property rights are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, materialism, and militarism are incapable of being conquered... A nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual death."

Those words were spoken April 4, 1967--exactly one year before his assassination. If you're an optimist, would you say America heeded Dr. King's words from 1967 to 2018?

H3: Again, if our human ancestors failed, if they were so stupid, why are you and I here?

H4: There are several possible answers to your question. You can go with W.E.B. Dubois's "Talented Tenth," you can claim humanity's perseverance greatly exceeded its compassion and intelligence...

H3: Why not just look at Kazuo Ishiguro's life? If most of our ancestors were stupid and greedy, how could they recognize and elevate a man like him? Surely you're being selective in your examples.

H4: I don't think I'm being selective in my examples. Didn't I say earlier that human beings used outliers to market and promote certain images?

H3: But it's not just him, a Japanese-born Brit. Look at Erica Wiebe, a proud Canadian with a German last name. Or Pakistani-American Shahid Khan. How can you look at these individuals and say the entire system was corrupt and everyone was in on it?

H4: I admit I was being overly general, but are you arguing we should focus on outliers in evaluating a culture?

|

| Melbourne, Australia (2016) |

H4: As you wish.

[Part 3 is HERE.]