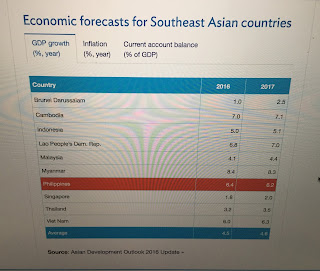

I started writing this article in Sydney,

Australia and finished in Denarau Island, Fiji.

|

| Outside the Hilton resort in Fiji |

I prefer Melbourne to Sydney—it’s more compact and has better public

transportation—but wherever you go, Australians are some of the most open,

friendly, and down-to-earth people you’ll meet (except in their airports, which,

like America, seem to require hiring citizens with the lowest IQs). In a city where slot machines and horse race

gambling are regular additions in bars and restaurants; brothels with mostly

Thai workers offer sex for 140 AUD while Australian dancers don't permit touching for less than 100 AUD; and marijuana

is essentially legal with a doctor’s prescription, you realize regulating man’s

vices can be done in ways that don't automatically remove the populace’s brains

or sense of adventure. (In contrast, in well-regulated Taipei, people—both

inside and outside of airports—are friendly but your

greatest danger is dying of boredom.)

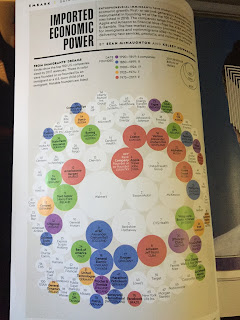

As Australia is the 17th country I’ve

visited in the last 5 months, I’ve noticed an interesting trend: cities that attract

affluent Chinese (or affluent or well-educated immigrants) see property and

other prices explode. It seems enterprising Chinese parents have cashed in gains from the

Chinese or Hong Kong stock markets and invested not just in Singaporean and Hong

Kong banks, but in property all over the world.

When I see smart, young Chinese adults with expensive American degrees helping their parents run a restaurant or hotel in

Indonesia, I’m torn between lamenting the loss of talent and realizing that

most college-educated Americans could not compete with the competence and

humility I see every day in Southeast Asia.

When I traveled 12 years ago, I saw mostly

European and American tourists. Now, I see

few Americans and mostly Japanese, South Koreans, Australians, Dutch (wanderlust

appears to be part of their very tall genes), and an increasing number of Chinese

tourists. (The Canadians can’t be far

behind, but you never know with them, since they tend to blend in politely.) [Update: see endnotes for more.]

In an age when images of American superheroes

like Captain America and Superman are ubiquitous worldwide on clothing,

backpacks, and toys, you realize the non-American countries haven’t yet figured

out they are the New World and the new frontiers—like it or not. I just saw an Aussie boy wearing American

flag socks and a Kobe Bryant jersey playing basketball. I asked if he was American, and he was not. (I wouldn’t wear a Dellavedova or Bogut

jersey, but there’s no excuse for not appreciating Patty Mills.)

America's propaganda machine is so good—it

better be, with no fewer than 17 intelligence organizations on the taxpayers’

payroll—it seems showing pictures of the Statute of Liberty and WWII

prevails over the changing facts on the ground, even as Canada, Turkey, Iran, Pakistan, Germany,

and other countries take in more Syrian refugees than America; elect Rhodes Scholars

who became self-made millionaires (as opposed to the 2016 Republican nominee,

who inherited millions of dollars); elect female leaders who speak out against

American surveillance long before Democrat Hillary Clinton criticized Edward Snowden as a lawbreaker and President Obama called him unpatriotic; increase GDP without

forcing residents to go into debt for essential items like healthcare and

education; build efficient, cost-effective public transportation; and open

doors carefully to educated immigrants. (In the meantime, America debates whether to directly accept immigrants who will bring much-needed technology

skills; indirectly accept them by granting outsourcing and technology firms a

higher visa cap; or not accept them and allow other countries to benefit from

their expertise.)

Some people ask me what I’ve learned over

the last 5 months traveling across the globe, starting in Colombia and ending

in Fiji. If you're interested, keep reading.

Democracy is Dead

Just kidding. I’ll save the politics till later. I’ll just say the Australian military member I met at a Sydney war

memorial knew more about the U.S. Constitution than most Americans, telling me,

“No one else but America has a [winner-take-all] two-party system because it doesn’t work.” He grew up working with his hands, a reminder elites in society don't hold a monopoly on knowledge or truth.

Go to Places where People Ignore Rules Crafted in Response

to Fear

Melbourne was one of my favorite cities—except

for the airport, of course. At

Melbourne’s airport, the customs official told me to put my phone away (because

putting phones away by the time you reach the customs counter definitely,

definitely prevents pictures and videos from being taken), then made the grand

gesture of holding my passport photo in the air and glancing at me, then

the passport photo at least twice. The

entire incident, minus the phone discussion, took about 5 seconds or, if

you prefer, two times longer than a mentally disabled person would require to

look at the passport photo as it was handed to her, remember it, and then

determine whether someone was trying to scam his way into Australia

with his biometric passport and Australian visa he applied and paid

for two months ago.

In any case, I loved Melbourne (for the record,

my favorite cities were Tokyo, Santiago, San Pedro de Atacama, Hong Kong, Melbourne,

and Jakarta. Yes, Jakarta. The food is amazing, and it’s the real “land

of smiles”—in about 5 years, when public transport arrives, the city will

become an easier tourist destination). Melbourne had an oddly familiar feel, and it’s not just because its Luna

Park area resembles Santa Cruz, California.

It’s because it felt and looked exactly like American pre-9/11—open,

unafraid, optimistic, and diverse.

Melbourne has a large, popular casino with all

the works, including a poker room with a neon sign flashing "Las Vegas" and a fancy food

court. Each area has at least one

security guard, and signs separating one area from another say bags

must be checked. The poker room had a large, ex-military-looking gent guarding

it, and I went to him with my bag open as doe-eyed as I could possibly be. In

America, I can sometimes get away with looking Mexican, Central American, or

Spanish, but in Australia and Southeast Asia, everyone’s first guess was

Arab. After the airport experience, I

was prepared to be strip-searched, but the gent gave me a wide smile and said,

“It’s ok, mate, I trust you.” The second

and third time I moved between areas without being bothered was when it hit

me—Melbourne is a city where people have kept their common sense. The large security guard saw me reading the

rules next to the entrance and must have figured out potential terrorists don’t

bother reading written regulations before making their move.

From that moment, seeing Melbourne and Sydney

made me sad. Everywhere I went, I was reminded of San Francisco and Santa Cruz,

but without Donald Trump or Sarah Palin as potential rulers. Government

unions in Sydney are doing the same thing as the ones in California—demanding greater

pieces of the tax pie and claiming if they don’t get the money, they

cannot guarantee safety. The Australians

shrug off such fear-based threats and focus on maintaining their existing 15

USD minimum wage and a healthcare system that covers all their medical bills

(but not their ambulance bill) for 1.5% of their income. That’s 1.5% of their income each year (the

military gent I mentioned earlier told me, “I don’t even notice it—comes out of

my regular paycheck.”). Their outgoing central banker, Glenn Stevens, gave such

a compelling, educational interview in the Australian Financial Review (see

9/9/16 edition), I promised myself I was going to read everything he

wrote.

I now know why George Soros—who is more often

right than not on macro issues—calls his programs “Open Society.” When you live in an open society, good things

happen organically, and people unafraid of each

other are more likely to collaborate spontaneously without meeting at the

same expensive universities. In Sydney, I met an

American dancer at a basketball shop who taught me more about fashion

economics than I learned in the last ten years. I would have never met him in America. He told me he’s moving to Australia under an immigration program

designed to attract workers under 31 years of age. He’ll be closer to his

Fijian girlfriend, too. Meeting him and

experiencing his optimism and energy firsthand made me happy for the rest of

the week. (Thanks, Maleek!)

Places that aren’t open societies or that spend

an increasing allocation of tax revenue on military or law enforcement

bleed and repel talent if the allocated tax revenue is at the expense of

non-law-enforcement job growth. Over

time, assuming options exist, the most open-minded or financially stable people

prefer to live in open societies, which also tend to be happier.

It is no coincidence that Melbourne and Sydney

are similar to two of California's most prosperous cities, Santa Cruz and

San Francisco. The formula is the same:

1. Attract law-abiding, hard-working

immigrants.

2. The immigrants bring new talents and/or increase

demand for essential services and items like housing, gasoline, groceries, insurance, and healthcare.

3. The increased demand boosts the value of existing residents’ houses, making them feel richer. (Ask yourself: why

have housing prices in American cities increased more in diverse rather than

non-diverse places, or near diverse places?)

4. Existing residents feel richer and spend

more money, increasing demand not just for essential services, but for

expensive coffee, clothing, etc.

5. A new creative class emerges, attracting young

people and more diverse jobs, such as website design, interior design,

etc.

6. The government sees a higher tax base and

increases government jobs, usually to people connected with political or real estate players, which again favors existing residents rather

than immigrants.

7. Everyone is happy…until the demand from immigration succeeds too

well, pricing out the next generation from housing and other markets.

After the last step, societies have a choice: a) they

can turn on each other, refuse to make sacrifices, and blame each

other; or b) they can try to increase mobility, spread out job growth not just in the large

and now-larger cities that have attracted immigrants (i.e., spread the wealth

geographically), and achieve a balance that militates against excessive

inflation in essential items like housing, college, and healthcare.

Existing residents usually split in two groups—the ones that owned houses before the immigration boom and the ones that rented. (You can guess which group blames the different-looking residents for their new problems.) [Update: while the Italians and Irish are similar enough visually to blend into societies together after both learn the official language, the same is not true with more diverse immigration, where a black African still cannot blend into a European country even after speaking the native language better than locals and wearing Nikes or Prada. One reason ASEAN will continue to be wildly successful is because immigrants can more easily blend in.]

By the standards mentioned above, America is the worst of all

developed countries—not only is it the only developed country appearing to

lack efficient and broadly available public transportation in its major cities,

it also requires its residents to go into at least five-figure debt to get essential items like a

college education. In most developed

countries, personal debt is anathema. Listen to Brad Katsuyama from Flash Boys (2016) talk about his

experience coming to New York from Canada: “Everything was to excess…I met more offensive

people in a year than I had in my entire life. People lived beyond their means,

and the way they did it was by going into debt. That’s what shocked me the most. Debt

was a foreign concept in Canada. Debt was evil. I’d never been in debt in my

life.”

Once I realized personal debt was necessary

to achieve a basic standard of living in America, especially for younger

people, I connected its increasingly authoritarian

society with attitudes towards personal debt. The Vietnam War saw numerous protests in America,

including ones where college students were shot and killed. Syrian and Libyan wars, in contrast, saw few protests and certainly not sustained or effective ones. Part of this change is obviously the lack of

a mandatory draft, but a society in debt or with excessive inflation in

essential items is not one that can buck the Establishment or established

political players, especially during a recession, when government spending

drives job growth.

I’m going off course again, so I’ll end this

section with a quick observation: the only airports I saw with the new scattershot

body scanners were American, Thai, and Australian. (The Thai airport personnel were nice, so the

American and Australian machines must come with a training manual titled, “Fear

is the New Black: How to Pretend to Be Military-Tough without Actual Military

Training.”) As some societies become more open, others are becoming more closed. It’s not surprising economic protectionism follows when people become more fearful of each other, unaware that the same

immigrants they increasingly fear are the precise reasons for their

economic growth thus far.

In my own way, I’m doing what I can to maintain

the vestiges of American rebellion (RIP George Carlin). In Santiago, Chile and every single other

South American airport, I took videos of the airport baggage area and sent them

to the TSA on Instagram with snarky comments such as, “Santiago is the most

prosperous city in South America, and its airport has plenty of tourists and

fancy shops, but they don’t have a TSA.” In Tokyo, my favorite city, it took

just 5 minutes from the time I exited the airplane to get past

customs/immigration, so I didn’t have time to take a video—now that’s

efficiency. [Update in April 2017: it took me about 10 minutes each to get through customs and security in the Dominican Republic and Costa Rica.]

Open Societies Don’t Care What You Do in Your

Bedroom

Ladyboys, transsexuals, sapiosexuals (if I see

that word one more time in a dating profile, I’m going to puke), and

homosexuals—what do they have in common?

In open societies, no one gives a damn about your sexual preferences.

In Bangkok, I was served by ladyboys wearing too

much makeup in grocery stores. In

Manila, a Muslim mall shopkeeper with a headscarf wearing sandals worked

alongside a Catholic wearing a gold cross and Nikes. In Fiji, the best servers

at my resort are 6’3”, 250 pounds, with waxed eyebrows and high-pitched

voices. There are red light districts in

prosperous Sydney and not-so-prosperous Bangkok—and like all red light

districts, they have delicious, reasonably-priced food available at

1:30AM.

We’ve talked about personal debt and excessive

or artificial/external inflation being the death knell of peaceful economic

progress, but the other consistent component of an open society is sexual

openness. Before France tragically

experienced terrorism, most news articles mentioning the country would discuss

the President's mistress or the copious amounts of sex (inside and outside marriage) French couples were having. Suddenly, the

articles shifted to cities banning full body swimwear (“burkinis”) and police

officers forcing Muslim women to remove their headscarves at beaches. (ISIS itself

couldn’t have created better propaganda showing Western hypocrisy on freedom of religion.) Which article

would you rather read—the one about a city council having nothing better to do

than pass a law allowing cops to harass old Muslim women on the beach, or the

President shagging a model with his wife’s permission?

After experiencing a traumatic event—especially

terrorism—societies and governments have a choice—they can remain open or they

can close themselves off directly (restrict immigration) or

indirectly (allocate more tax revenue to unnecessary military expansion, whether

domestic or international). I’ll give

you one guess which direction much of America has chosen. (If you're an Aussie airport employee, you

can have four guesses--I believe in leveling the playing field.)

Successful Societies Maintain Informal Norms

Not following stupid rules, using common sense,

and letting people have sex in peace create a natural segue into my next topic:

the informal vs. the formal, or “How Did We Allow Lawyers and Insurance

Companies to Set Behavioral Norms?” (aka What’s Behind the Rise of Donald “I’m Not

Politically Correct” Trump?)

|

| Counterargument in Duncan J. Watts' Everything is Obvious (2011) |

I’ve mentioned Dan Ariely’s book, Predictably

Irrational (2008), before. Ariely discussed an Israeli daycare’s late

pick-up policy. Initially, a few parents

were late picking up their children, causing the daycare to incur overtime. In an attempt to minimize disruption,

the daycare instituted a penalty for late pickups. Each late interval incurred a fee. What happened next? Late pickups

*increased*. Ariely’s accomplishment was

figuring out why.

Ariely determined that before the penalty (which

could also be called a rule or law), social norms rather formal norms

prevailed. Ariely called it “shame,” but

whatever you want to call it, it worked better than the rule-based or legal

system. Basically, when you trust

people, they usually rise to the occasion unless other incentives

interfere. The minute you get lawyers

involved, people start doing cost-benefit analyses and try to “game” the

system. In the case of the daycare, they

will have to add more rules (higher penalties, shorter intervals etc.), which

function as amendments without any end. All

too suddenly, a new law or rule becomes more complex and convoluted and still

doesn’t deliver the intended result. As

Michael Lewis wrote in Flash Boys (2014), “Every systemic market injustice

arose from some loophole in a regulation created to correct some prior

injustice.” (Bonus: "As a law professor... I certainly understand the law and the rules. And one of the things I understand is that you can't write a law that I can't get around." -- Michael Josephson)

Go look at any random American civil

code. Observe the numerous subsections, which usually indicate a lobby group or

group of concerned citizens have, over time, exempted themselves from the law’s

purview or at least minimized its bite. What’s that? You say some new laws protect more people, such as

transgendered people? Ask yourself: in the absence of express diversity quotas,

is a small business owner more or less likely to hire someone who can sue him

for discrimination, or someone who looks like him and who belongs to the same

religious institution? If the latter, does such a dynamic mean that small employers are encouraged to hire minorities (whom the law intends to help) after they’ve hired

everyone they know and only when demand quickly escalates beyond what they

anticipated?

Creating too many rules or laws almost guarantees—in the absence of an irreverent, anti-authoritarian

culture—people will more likely do the minimum required by law, because lawyers have interjected themselves in a social norm and overruled it

by fiat. Sure, we have the Queen and her progeny as a useful conduit to

establish social norms in the U.K. and to take attention away from Englishmen

with bad teeth and out-of-shape British women, but when lawyers set too many

social norms, they take away personal initiative, and societies become

apathetic. Indeed, more laws don’t mean

the intended goal of the law will be achieved or even promoted—it could mean

that people see the law itself as an excuse or barrier to acting on their

own. Meanwhile, in Japan or South Korea,

social norms often prevail over legal ones, so any older male can be an authority

figure, not just the police.

I experienced this dynamic myself when I did

pull-ups on the train—an older Japanese man tapped me on the shoulder and made a disapproving gesture. In a movie

theater, I had temporary restless legs syndrome, and an older Japanese man

three seats down reached over and gently put his hand on my leg, indicating I

should stop. In Seoul, a

Nigerian-American teacher told me, “The police here [in South Korea] have little power—I’ve seen older Korean men overrule the police and tell the police what

to do, and the police complied because the man was older.”

Thinking about this social dynamic provides more insight into why some Asian countries, like Japan, are opposed to mass immigration. It’s not xenophobia or racism—it’s because

they haven’t figured out how to maintain their harmonious social norms, which,

in the case of Japan, have led to one of the most peaceful, polite, safe, and efficient countries in the world.

No system is perfect, and an obvious flaw exists in this particular norm system—older men aren’t exactly a diverse

demographic when it comes to enforcing rules, and having every man over 50

years old as a potential enforcer doesn’t help foster a culture of creativity

or innovation. Japanese women seem to be

quietly rebelling against the “older men as social enforcers” dynamic by

refusing to have kids and using the Japanese yen’s strength to study abroad and

travel as much as possible. (A big shout

out to the Japanese study abroad students who took me to Melbourne’s St. Kilda

beach and took fun pictures with me, a random stranger they’d just met in a

cafe.)

At least under the Western system, you’ll have

more women and minorities able to have a voice and shift the culture. Yet, is that really true? The point of the

law is to create a predictable system. If the male judge in Courtroom A interprets an anti-discrimination law, a witness’s credibility, or the admissibility of a piece of evidence differently than the female judge in Courtroom B, then

justice is determined by the random assignment of a judge or a random judge's subjective beliefs about what juries should see. In addition, most American judges are older

men anyway.

Look at your average police

station—mostly white men (though cities are becoming more creative and

appointing more minorities as public faces of their departments, which looks

good but does nothing to change the dynamic for 80 to 90+% of the employees and

the residents with whom they interact). Your average K-12 district? Mostly white female teachers. (From Ed-Data in 2010: "In 2008-09 California’s teachers were predominantly white (70.1%) and female (72.4%), quite a different look from the student population that was 51.4% male and had major ethnic categories of 49.0% Hispanic, 27.9% white, 8.4% Asian, and 7.3% African-American.")

At the end of the day, are the Western and

Eastern systems really so different? And shouldn’t the question be how to create a society as harmonious as

Japan, but with more input from everyone, not just older men? As a Canadian told me in Taipei, “Things

changed when we stopped caring about each other.”

Formal Norms Destroy Harmony as Lawyers and

Government Enforcers Take Over Society and Divert Tax Revenues into their

Pockets

Worst of all, as more laws are passed,

the more funding x group demands to enforce such laws. Soon thereafter, society becomes increasingly fragmented as

existing political players are scared by the potential threat to their own

funding and use their media connections to attack the new players (see, for

example, traditional K-12 districts vs. public charter schools—I mean, God

forbid students in failing or inner city schools be allowed options); the

entity receiving new funds does whatever it takes to make sure it can sustain

its new funding (if it cannot produce objective results, then it usually relies

on fear or presumed heroism by highlighting outliers); and people still not

part of the government's largess have no choice but to use victimhood, whether

real or imagined, to gain equal access to government-fueled job growth or at

least to prevent themselves from being used by others to justify government

funding.

For example, see Ferguson, MO, where studies have shown the poor and

politically-disconnected are fined at alarming rates to maintain government

jobs or government job growth, or intentionally segregated:

Exploitation "is in turn made possible by residential isolation. Ever since the creation of the 16th-century Venetian ghetto, the physical separation of a dishonored group has served to shield the larger city from the consequences of disinvestment in the marginalized area, and to shift the blame for the conditions in the community onto the dishonored group. The maintenance of segregation--by race or class or religion--permits the cycle of neglect to continue." (The Atlantic, June 2016, page 37, Patrick Sharkey.)

By the way, it’s not just government that’s

fragmenting society with its funding demands and overreach into private lives—private

companies are destroying their reputations when they use metrics designed to

measure performance but which, like most other rules, become gamed over

time. The metric becomes the goal rather

than the service. (See Goodhart’s Law,

which Ruchir Sharma explains in The Rise and Fall of Nations (2016):

“[O]nce a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be useful, partly because so

many people have an incentive to doctor numbers to meet it.” I’d add that metrics cannot capture

intangibles essential to customer satisfaction and therefore the long-term

viability of a brand.)

I tend to focus on government actors rather than

private sector bad actors. Fiji Airways (love the English subtitles and captions in your

in-flight movies, but still waiting on your response to my complaint about the

Sydney airport fellow) and Starbucks might give you terrible customer service,

but their employees won’t come into your home, shoot your dog, and still keep

their jobs if they act on a bad anonymous tip. With corporations and businesses, the key is to focus on externalities

and the environment, which is another way of saying that banks and natural

resource companies need to be heavily regulated but without applying the same

level of scrutiny to other, more productive and more innovative

businesses. Sadly, the American government

is also inept in this area—it not only failed to catch Enron’s financial

shenanigans, it actually approved one of its accounting methods, and according

to Michael Lewis in Flash Boys (2014), the “only Goldman Sachs employee

arrested by the FBI in the aftermath of a financial crisis Goldman had done so

much to fuel was the [computer programmer] employee Goldman asked the FBI to

arrest.”

Innovation, Immigration, and Debt-Fueled

Development

As I wrote above, cities that attract the best

or hard-working immigrants win economically, at least for one or two

generations. It’s not a big leap to go

from cities to countries and to realize that absent some exceptions,

immigration has been responsible for *all* of America’s and Britain’s post-WWII

success (one could even argue that a German-Jewish immigrant, Einstein, along with immigrant Leo Szilard, helped

win WWII with nuclear innovation).

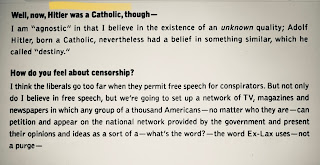

Economists, philosophers, writers, pundits and

academics, like everyone else, are subject to confirmation bias or other

biases. They see their country’s new

prosperity and, absent a clear breakthrough such as the discovery of new

natural resources or technology, attribute it to a particular way of doing

business (“What’s Good for GM is Good for America,” which then morphed into

studying the “superior” Japanese business model); a particular leader (Winston

Churchill or Harry Truman); and/or a particular religious construct (the Protestant

work ethic, Judeo-Christian values, etc.). The last one always baffles me, because Christian/Catholic antipathy and discrimination against Jews has been well-documented and includes

much more than just Reichskonkordat and ordinary Germans juggling church and National Socialist meetings. From the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum website: in 1933, “Almost

all Germans were Christian, belonging either to the Roman Catholic (ca. 20

million members) or the Protestant (ca. 40 million members) churches.”

|

| From Warren Hinckle's If You Have a Lemon, Make Lemonade (1974) |

If I’m right about immigration, then the rise in

demand I discussed earlier because of new residents is the real source of Western

prosperity, not any type of after-the-fact theorizing, especially when you add

debt to drive economic development. Stated

another way, what if most Western post-WWII economic growth is a simple

combination of immigration plus increased bank, VC investment, and corporate

loans? Think--the easiest way to

increase demand (and jobs and tax receipts) is to pump more money into a

country’s economy. As long as that

additional dollar keeps making the rounds, from the business owner to the

employee to the local café

owner to the local mechanic and to the restaurant owner, it will become four dollars

without any need for innovation, further addition, or unique competitive

advantage. With enough debt, any economy can be transformed from supply-driven

to demand-driven. Adding immigration and

marketing to debt turbocharges the sleepiest of hamlets—at least for a

while.

At some point, however, especially if wages don’t rise with the cost of essential items, issuing debt has less economic

impact. Businesses may continue to use

loans to cushion themselves against unpredictable cycles, but the dollar of debt no longer circulates four times, enriching all who come in its path—it may

not even move at all if lower interest loans are used to pay off earlier,

higher interest debt.

You

might be asking yourself, "What does this have to do with his travels?" Every single prosperous Western city I’ve visited in my life has been diverse,

with many first generation immigrants. I don’t think it’s a coincidence. In

fact, the only two major advantages I see Western societies having over

Eastern societies are diversity and materialism. Materialism is a funny way to describe an

advantage, but once you realize Western economies rely on consumer demand

to drive job growth and use debt as a growth turbocharger, it’s obvious why Western governments and central banks are doing whatever they can

to re-generate the money flow. Is this model sustainable in the absence of

continued immigration?

Now What?

Far be it from me to suggest having 2,391 different

kinds of sodas isn't the pinnacle of Western prosperity, but seeing different

systems work in different countries makes you listen—I mean, really listen—to different

viewpoints. Many Asians I met told me, “You Americans have too much freedom.”

If you have excess order, you still have order, but if you have excess liberty, you have chaos. -- Will Durant, historian

They meant they’d rather have a little less

freedom to say whatever they want in exchange for much more harmony and

peace. One lesson is that fewer

options don’t necessarily translate into worse-off societies if government attracts intelligent people.

In Chinese culture, the state is preeminent. Better a year in tyranny than a day in anarchy. Order is everything in China. -- Michael Wood (2020)

When I scored an upscale resort room

in Hilton Fiji Denarau (after 15 years of saving AMEX points, it seemed like a

good time to use them), I finally figured out why people pay so much more to

isolate themselves from the locals. When

I travel, I always try to stay in areas where the locals live, or I just get an

Airbnb. Resort areas are essentially the same, so what’s

the point? Well, the point is that you’re around people who can afford to be

there, so it feels safer and more cozy—you might even make a business

connection or two. It goes without saying the sunsets and rooms are exquisite (My Hilton beachfront room had a shower AND a large bathtub). You’re also around

staff who are super-nice to you because they have the best-paying job

for miles. I suppose financially-incentivized kindness is better than scorn or apathy, but I still

say the food is always worse and more expensive in resort or beach areas, and I’d

rather have access to a 5 to 10 USD foot massage in a run-down strip mall than

a 50 USD one in a fancier ambiance. Once

every 15 years ain’t a bad time to hit up a fancy resort is all I’m sayin’.

[While we’re on the subject of companies, the

most useful apps were Airbnb, Agoda, Uber, Couchsurfing (check out the events,

which include walking tours), Tinder, iTranslate (paid version), Google

Translate, Orbitz, my banking app, AMEX (to pay my recurring bills back home,

like my Netflix account), and various messaging apps—WhatsApp, Viber, WeChat,

and Line. Many people recommended Grab,

which is similar to Uber. When I get

back, I’m getting the iPhone with the largest memory capacity—16 GB wasn’t

enough for all my pictures, apps, and videos. T-Mobile's worldwide roaming plan was fantastic--it saved me from having to buy SIM cards in every new country, though I was sometimes stuck with 3G rather than LTE or 4G. (Update on February 2018: after about two years of using T-Mobile's international roaming plan, it was unexpectedly canceled.)]

Regarding airlines, LATAM Airlines was the best in South America. For shorter trips, budget Air Asia was just fine. I'd avoid Avianca, Qantas, Blue Panorama, Lion Air, and Fiji Airways. Use Virgin or Virgin Australia instead.]

|

| Seen January 10, 2019 on LinkedIn |

|

| Told you not to use Avianca. |

I’ve already told you one other lesson: informal

systems can and often do work better than formal systems in creating harmony

and psychologically healthy societies. Despite not including metrics like opioid prescriptions per capita in

their statistical analysis of success, formal systems should

work better at allocating capital and allowing knowledgeable workers greater

access to higher wages. In Jakarta, which

had the best and most interesting food and tea I’ve ever had (even better than

Singapore’s hawker stalls), I met a college-educated woman making about 4,000

USD a year working 40 hours a week with a 3 hours daily commute. She spoke fluent English, French, and Bahasa

Indonesian and used to work in a foreign embassy. Another woman I met in Cebu, Philippines had

an MBA, spoke perfect English, and was smarter than most Americans I’ve met. She makes 7,500 USD a year (not including expense reimbursements) managing upscale pizza franchises in several cities.

Put either of them in any country that favors a

formal system, and they’d make at least 40,000 USD—but would they be happier? I

suppose it depends on how well infrastructure improves, cutting down on commute

time and pollution levels—and whether they feel as if their skills are rewarded appropriately and whether their children have

greater opportunities than them. Many smart people I met overseas wanted to go

to Canada or Australia, or, as a third option, America. The 21st

century seems to be defined by jobs and taking risks to get better pay, which

benefits the destination country (as I explained above) while boosting the

earning capacity of the immigrant. Countries that don’t value their smart workers,

especially their female ones, are going to lose them. (Believe it or not, getting a job in an

upscale mall in the Philippines may require a college degree—to guarantee

the worker speaks fluent English to satisfy tourists—and student loans don’t

really exist in developing countries.)

In any case, the informal vs. formal is the

lesson I keep returning to. In

developing countries, which often lack paved roads near their beaches, drivers

honk horns to warn pedestrians they’re coming or the car in front of them that

they’re about to pass. Despite traffic too zany for me to ever contemplate driving in any SE Asian developing

country, I never saw any driver honk his horn in anger at another driver. Once, when there was a miscommunication, two

drivers waved repeatedly at each other, honking horns to signify contriteness, a

symphony of apology.

|

| Contrast with Germany. From Nat'l Geographic (Dec 1961) |

Conclusion

I’ll leave you with my favorite quote from my

travels, from a Filipina woman who had a keychain in the shape of a dildo. When

I asked her about it, she remarked, “I don’t understand people who don’t like sex

or who don’t like talking about it.

Where do they think they came from?”

Where, indeed?

© Matthew Mehdi Rafat (2016)

Update 1: I realized I didn't mention South America much. Rio was overrated, though its Botafogo neighborhood had some interesting cafes and bookstores. I also enjoyed the Cinelândia area. Both Botafogo and Cinelândia take 1/2 a day to see each, though Botafogo is best seen on a Friday or weekend evening. (I didn't go to São Paulo, and every Brazilian I know swears I'd have a different opinion of Brasil if I visited its commercial center.)

Cartagena's old town is romantic and worth a one-day visit. Medellin, situated in a valley and therefore cooler than most Colombian cities, has much potential. Overall, however, Colombia needs so much infrastructure, I see no reason to return in the next 10 years. My worst airport experience was in Colombia, where Colombian-based Avianca airline staff misled me. I had to call a Colombian friend in California to assist me and was charged twice for a replacement ticket--no small sum. Although Avianca is one of South America's largest airlines, for safety and convenience purposes, I'd avoid them and choose LATAM or Copa instead.

Buenos Aires, Argentina is a fun, vibrant place and not as expensive as Chile. Many tourists enjoy the trendy Palermo neighborhood.

Colonia, Uruguay--accessible by Buquebus--is a cute little hamlet.

Chile was my favorite South American country and also the most "advanced." It doesn't seem a coincidence that Chile was able to "re-set" many of its problems after Pinochet's often brutal regime.

Perhaps there's another pattern worth following: after various government agencies gain too much unchecked power, they often become ineffective or arbitrary despite their increase in power. (Absolute power corrupts, remember?) At that point, a strongman ruler is more likely to get elected or ushered in by a coup--whether in Turkey, the Philippines, or America--and the people, fed up with ineffectiveness and corruption, give license to extrajudicial measures, as long as they feel the ruler is trying to clean up the mess. ["People will put up with corruption as long as it works." -- Alan Beattie, False Economy (2009)]

|

| Mexico's "strongman" ruler was in power for 30 of the 34 years between 1877 and 1911. |

The psychological effects of the new, often politically incorrect politician are immediate--people are energized because they feel as if their voices have been heard. I've visited the Philippines several times. After the Philippines' recent election, I was struck by the chasm between what I was seeing and feeling in the country--renewed optimism and hope--and the media's reporting of an out-of-control politician. The Philippines' Duterte is a lawyer who's taken on the Catholic Church and mining companies and spoken in favor of environmental regulation and women's rights. (Just goes to show you--you can't trust the media. Get out there and see for yourself before making any conclusions.)

I'm guessing the positive mood was the same in Turkey after the July 15, 2016 attempted coup, when people came out in droves to support the existing president, who then removed thousands of government employees allegedly involved in the coup, including teachers. Do years of static government consolidation require a strongman to use extrajudicial means to clean up shop?

Seeing lithium miners' poor living conditions in one of Chile's most visited tourist towns indicates that a strongman may be able to reverse stagnation and corruption, but the long-term picture is not clear. In an ideal world, people would realize how lucky they are to live in relative peace and do whatever it takes, including self-sacrifice, to never reach the point of needing a strongman ruler.

Update 2: I originally thought I'd been traveling for 6 months straight, but someone told me it's about 5 months straight--from April 22, 2016 to September 16, 2016, or 147 days.

Update 3: right after I wrote this post, where I mentioned not meeting many Canadian travelers, I met a Canadian solo traveler in Fiji. She lives in New Zealand as a dental hygienist. She’s going back to visit her family for X-Mas because she’s yet to adapt to sunshine in December and no natural fir trees. As is the case with most of the non-Eastern-European white women I’ve met, the conversation ended abruptly after I questioned one of her statements. I realize the line between playful mocking and polite criticism can be a fine one, but no other culture except the one practiced by educated Western white men and women seems so sensitive to having clearly incorrect statements contradicted. Such cultural uniqueness, even if not as widespread as I believe, is causing a backlash in many developed Western countries, where anti-political correctness movements may take unexpected turns, especially against politically vulnerable ethnic or religious minorities. Stated another way, there is no Indonesian equivalent to America's Andrea Dworkin. In fact, much of Asia's religious symbolism and therefore its culture revolves around men and women's interconnected natures. (Fun fact: literally translated, the expression for "thank you" in Bahasa Indonesian means "accepted/received with love.")

In any case, after a conversation about our travels, the educated Canadian said that Australian *airport* employees were “smart” because they recently caught two Canadian girls smuggling in millions of cocaine. I pointed out Australia was in the middle of nowhere and didn’t have land-based borders, so assuming its Navy was on the job, it was easier to prevent drug trafficking, and in any case, it wasn’t the Aussie airport employees per se who would catch the drugs—it would be trained dogs. She persisted in defending the Aussie *airport* employees and after she left, I looked up the incident. Yup, it was an international effort and drug-sniffing dogs caught the enterprising Canadians. The two Canadians—both under 30—weren’t criminal masterminds, either, as they went on a very expensive cruise and posted Instagram pictures of their travels. I think I may have crossed the line when I added that the Aussie government isn’t going to report their failures in catching drug smugglers, so the only ones she’ll hear about would be the occasional successes and again, drug-sniffing dogs and basic surveillance—not Aussie ingenuity, which has yet to lead to a country-specific cuisine or Aussie-made technology used widely beyond its borders—would be responsible. [Update: Stephen Le's 100 Million Years of Food (2016) discusses some Australian attempts to incorporate its indigenous population's cuisine into more mainstream fare, so perhaps there's some hope for Aussie cuisine.]

I declined to say that even Canada managed to invent Blackberry and Lululemon, and what have the Aussies ever done for us (outside of mining)? Just to be sure, I looked up Australia’s number one technology company. It’s Atlassian (symbol: TEAM), founded in 2002, with 1,700 employees worldwide. (Yeah, I never heard of it, either.) One gets the sense white Western culture depends on not looking like a fool even if richly deserved, which would explain why the U.S. wouldn’t issue any comment on the Chilcot Inquiry and is increasingly becoming like a cranky old man refusing to admit that he just fell asleep in his lounge chair or made any other mistake, ever.

Update 4: from The Pew Center, "Modern Immigration Wave Brings 59 Million to U.S., Driving Population Growth and Change Through 2065," Lopez, Passel, and Rohal: "Between 1965 and 2015, new immigrants, their children and their grandchildren accounted for 55% of U.S. population growth. They added 72 million people to the nation’s population as it grew from 193 million in 1965 to 324 million in 2015...The combined population share of immigrants and their U.S.-born children, 26% today, is projected to rise to 36% in 2065, at least equaling previous peak levels at the turn of the 20th century."

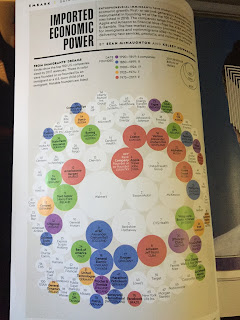

|

National Geographic magazine, seen on airplane in January 2019.

Note that the man who raised Jeff Bezos was a Cuban refugee. |

Update 5: my Taiwanese friend just told me Taipei is the most "laid back" developed Asian city--a welcome contrast to my satirical comment above about boredom.

Update 6: looks like Berlin, Germany is doing well on at least one metric.

|

| From May 2019 |

Bonus: an earlier post about my travels is HERE.

March 2017: Toronto is HERE.

June 2017: Cuba is HERE.

August 2017: Cebu, Philippines is HERE.

September 2017: Brunei is HERE.

September 2017: Yogyakarta, Indonesia is HERE.

September 2017: Abu Dhabi (UAE) is HERE.

September 2017: Oman is HERE.

September 2017: Qatar is HERE.

October 2017: UNWTO's 2017 Conference is HERE.

October 2017: Istanbul, Turkey is HERE.

December 2017: a summary of travel post links is HERE.